The Wind Called My Name, A Conversation with Mary Louise Sanchez

- H. Rae Monk

- Apr 1, 2021

- 8 min read

During the past five years, the Following the Manito Trail project has documented the stories of Manitas/os through oral history interviews, conversations and correspondences. And there is a definitive trend. Querencia is at the heart of every Manita/o tale, whether in tangent with family, land lost or maintained in New Mexico, or in the new communities of the diaspora throughout the American West. Querencia for Manitas/os is the string that ties ancestor to progeny, keeping tradition and family alive. This is evident in Mary Louise Sanchez’s middle grade novel, The Wind Called my Name (288p. Lee & Low/Tu Bks. Sept. 2018. Tr $18.95. ISBN 978162014780).

The story, loosely based on the people and experiences of Mary Louise’s mother and her family, follows the pre-teen Margarita as she travels from the Mora County mountains of New Mexico to the Wyoming plains of Carbon County. They leave behind beloved family members whom they commit to sending money back to in order to pay the taxes on the family land. When Margarita’s older brother Alberto suggests selling the land, Abuela says poignantly, “No. Es mi querencia.” As her family leaves, Abuela continues emphasizing her love for her beloved homeland, “The bones of my family are here. I must try to save it. New Mexico is my home-our home. It will always be here for you if you want to return” (pg 3). Though Mary Louise was born and raised in Wyoming and now lives in Colorado, she and her family are yet another example of the Manita/o diaspora and her stories resonate with the heart of our project.

Here is Mary Louise’s conversation with H. Rae Monk, a friend of Following the Manito Trail.

H. Rae Monk: In your novel you refer to querencia in your main character’s conversation with her grandmother on page three. Could you tell me about where you personally feel a pull of querencia as a result of being away?

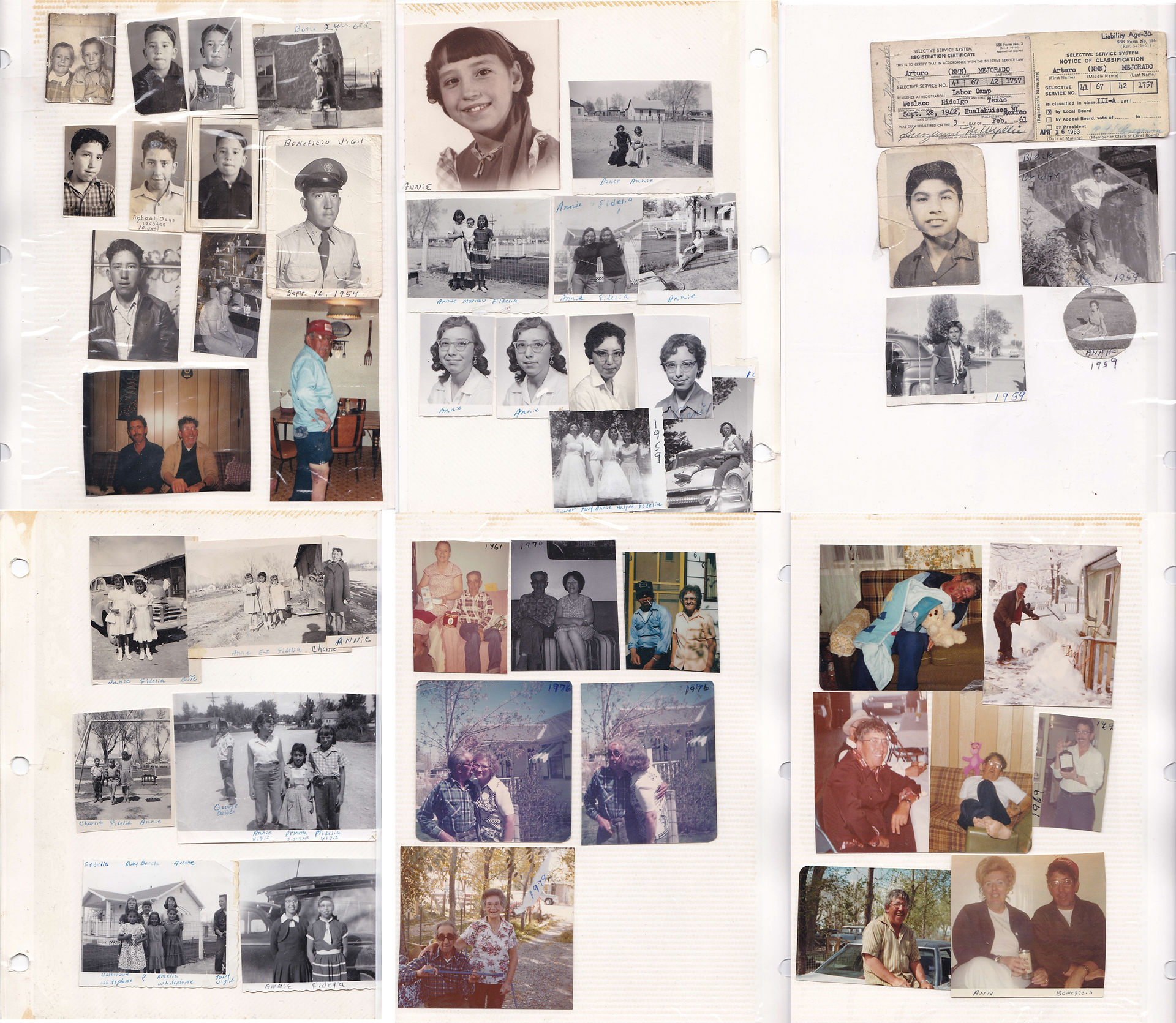

Mary Louise Sanchez: In my book, it’s ironic that my great-grandmother, Cruzita Cardenas Sandoval, said these words about querencia, but ended up being buried in Rawlins, Wyoming not long after moving there with my maternal grandparents in the 1950s. My other great-grandmother, Rufina Maldonado Maes, lived with my maternal grandparents in Fort Steele from the 1920s until she died in 1948. Both of these great-grandmothers are in the same cemetery in Rawlins.

My mom and dad have quite a few common ancestors in New Mexico, so New Mexico is in my DNA and in my heart. When my Gonzales grandparents moved to our town, we often saw both sets of grandparents visiting each other formally on Sundays. We always knew our grandmothers were cousins from the Mora area. Because of their common Maes lineage, they are fairly close cousins and this bond also makes me care deeply for Mora and its villages.

When we have visited Spain and Portugal, I’ve also experienced that sense of querencia there too.

H. Rae Monk: What were the most beloved traditions your parents brought from New Mexico? What traditions did you create that were purely Wyoming? Have these traditions survived to the next generation?

Mary Louise Sanchez: Sometimes I believe when you are the diaspora and have left your home, you are more zealous about maintaining your traditions. My maternal grandfather, Filadelfio Sandoval continued the matanza tradition by slaughtering a sheep in the spring. Then the women prepared burranates and even menudo from the animal. Many of our meals were New Mexican and fit the seasons: lamb; Chile Colorado with pork and even potatoes; lentils; havas (which both grandfathers grew in their gardens); empanaditas; arroz con leche; capirotada and other dishes. Vendors came from Colorado and New Mexico and seemed to know which families would purchase new beans, chicos, and green chile. In the spring we collected quelites near the banks of the North Platte River and my mom made fresh cheese—but not from goats like she wanted to make. My Sandoval grandfather ate cottage cheese with chokecherry jelly or molasses for dessert, probably because there was no goat cheese in our town. We still make chokecherry jelly and continue to prepare New Mexican dishes.

On Sunday afternoons we listened to a radio program, The Spanish Hour. They played New Mexican music. We also attended many weddings where La Entriega was sung and wedding dances always started with La Marcha. I am the proud owner of a Rio Grande blanket that my paternal great-grandmother wove. My children, nieces and nephews have knelt on it as my brother, on the guitar, accompanied my sister and me as we serenaded the wedding couple with La Entriega.

My dad was a great storyteller and modernized La Llorona, adding a car in the story. In my collection of New Mexican books, I’ve read some of the stories my dad told us. I share some of the old stories with students when I teach about Hispanos in Colorado history.

When we visited older relatives there were always stories about ancestors. Thus, my siblings, cousins, and I grew up knowing who we were related to in the past and even in our town through the family stories.

My maternal uncle graduated from the University of Wyoming during the Great Depression and my siblings and our children have continued the tradition of attending the school. I continue to serve lamb, especially at Easter time in honor of my sheepherding family in New Mexico and the strong sheep industry in Wyoming.

My mother’s addiction to genealogy was passed down to me. Her maternal side has deep, deep roots in old Albu(r)querque with some of these familiar family names: Baca, Barela, Duran y Chaves, Hurtado, Ruiz, and Silva. My dad’s family has Mora county roots, as do some of my mom’s roots. By doing genealogy I’m continuing the tradition of learning about our family and its history and sharing the information.

H. Rae Monk: What role did religion play in your home? Margarita and her family have nowhere to attend services. Did your family have the same issue?

Mary Louise Sanchez: My mom used to say she was an Ecumenical Christian because she attended the local churches in Fort Steele, Wyoming with her friends, since there was no Catholic Church there. When she married my dad in Rawlins, she started attending the Presbyterian church with his family. My Gonzales family converted to that religion because my divorced paternal grandfather and my grandmother were not welcomed in the Catholic Church when they married.

When my Sandoval grandparents moved to Rawlins, they were able to attend mass. My siblings and I were always exposed to Catholicism because of our Sandoval line, even though my immediate family attended other churches. When my sister and I married, we embraced the church of our ancestors, as did our other siblings. I’m even a graduate of the Catholic Biblical School after a four-year program and have taught classes.

H. Rae Monk: Your novel focuses on the family attempting to learn English, but still speaking Spanish in the home and for religious purposes. What was the role of language in your mother’s childhood home and how did it reflect on yours?

Mary Louise Sanchez: My mom was born in Wyoming, unlike the story I wrote. She and her siblings were encouraged to speak English and because she was one of the younger children, English was her primary language. In fact, she used to be confused as to how to address her grandmother every morning. She said she would get mixed up with “le” and “te” in the familiar greeting, “Buenos días (le) (te) Dios. My mom also said she learned to speak Spanish more fluently when she married our dad. Unfortunately, both sets of grandparents spoke to us in English, rather than insisting we speak to them in Spanish. I studied Spanish in high school and college, and I could discuss the poetry of Lorca on paper, but my skills in speaking orally with confidence have much to be desired.

H. Rae Monk: Margarita goes to school in a one room classroom, what was school like for your mother, whom the story is based around and what was your schooling like?

Mary Louise Sanchez: My mom was a good student and especially enjoyed reading and history. She praised her teachers for giving her a good education. She said one teacher would put records on the Victrola and the kids would practice slants and ovals to the rhythms of the latest songs. My mom had classmates of diverse ethnicity. When she was around age thirteen, she remembered how sad it was to see some of her Japanese-American classmates having to leave Fort Steele because of what happened at Pearl Harbor.

My parents emphasized the importance of education and we had models of two university graduates on both sides of the family to follow. In first grade I missed six weeks of school due to measles and mumps, but it didn’t affect me, because I had already snuck a peek at the end of our Dick and Jane basal readers where there was a real story that I read. I’m sure my classmates were still studying sight words and phonics in my absence. In third grade I remember reading the book Heidi and vowed to see the Alps during my lifetime—and I did!

I followed the college preparatory tract in high school and was consistently on the honor roll. I also was active in school clubs and activities, especially music, where I performed in competitions.

My parents were my primary educators by giving us subscriptions to children’s magazines, modeling reading at home, and making sure we had and used our library cards! Our parents also gave us piano lessons, paying for them by my mom cleaning the piano teacher’s house. They bought me a piano when I was four years old because I showed a talent of being able to play by ear—like my dad. I also had a beautiful child-sized accordion and later I had a clarinet which I played from elementary school through my college years.

H. Rae Monk: Did your parents ever take you to visit New Mexico? If so, who still lived there? Do you visit as an adult?

Mary Louise Sanchez: Our Gonzales grandparents lived in Chacón, New Mexico and we visited them there when I was very young. In the 1950s, my strongest memories are of visiting them on the campus of Menaul School in Albuquerque where our grandfather was the night watchman and laundry man. Our uncle and aunt were students at the school. We also visited my dad’s uncle and cousins in Mora, New Mexico.

Before my great-grandmother Cruzita Cardenas Sandoval moved to Wyoming before her death, we visited her in the village of El Carmen. One memory of that visit was that we went outside and watched her milk a goat, and then we drank the warm milk. I didn’t appreciate it at the time, and now I’ve been on a quest for some time to find unpasteurized goat milk to make my own fresh goat cheese or at least to eat it.

As an adult I enjoyed visits to New Mexico to see my dad’s childhood home through his eyes; and seeing churches with my mom where ancestors were baptized and buried. On one visit with my mom, she knocked on a door of someone who had goats in their yard. She shared family stories and ancestry with these strangers, who suddenly became friends, as she waited for them to make her the fresh goat cheese .

Now, we escape to New Mexico as often as we can because our daughter lives in Albuquerque. I like to tease her that she lives on her ancestors’ land because our roots run deep there.

--

Mary Louise (Gonzales) Sanchez grew up in Wyoming, where her family continued to celebrate their rich colonial New Mexican and Hispanic heritage, with its deep roots in the U.S. going back to 1598. Her love of history, genealogical research, and other in-depth studies have given her the places and names in her narrative and a passion for telling the stories of her ancestors and others like them.

Keep up with Mary Louise on her website, marylouisesanchez.com

The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators honored The Wind Called My Name for one of its three inaugural On-the-Verge Emerging Voices awards in 2012. In 2016, her novel won the New Visions Award from Tu Books, an imprint of Lee & Low Books, making the publication possible. In 2019 the novel was a finalist for the WILLA award in children’s fiction and non-fiction sponsored by Women Writing the West. This award is named for Willa Cather. She wrote Death Comes to the Archbishop, whose antagonist was based on Father Antonio Jose Martínez. Father Antonio baptized Mary Louise’s great-grandmother, Rufina Maldonado Maes, in 1848. Her baptism record lists all her grandparents, along with maiden names. This line has many settlers of old Albuquerque.

Mary Louise Sanchez also has a forthcoming picture book through Eerdmans Publishing titled, A Young Santero’s Journey. The book tells the story of a young Benito Ortega who wants to be a santero like his ancestors, especially as he is named for Benito Ortega, a renowned santero who carved a bulto of The Holy Family.

Comments