Querencia On and Off the Manito Trail: 3 Part Series

- Margarita E. Pignataro

- Jul 7, 2021

- 12 min read

Following the Manito Trail

Permission

Margarita E. Pignataro Ph.D.

University of Wyoming

School of Culture, Gender and Social Justice

Yet to see the Creator’s wonder, the mountains of Encampment, Wyoming, I write from afar. Yet to experience the arborglyphs displayed and carved by the Manitos, I ask permission to share my perspective and for entry in the path of all who have made, are making, and will make a difference in the Wyoming territory and communities.

Illustration 1 Annals of Wyoming: The Wyoming History Journal “Making Heritage and Place on Trees: Arborglyphs from Latina/os in Wyoming” Spring/Summer 2017 89:2&3 (121). Caption reads: “A few of the thousands of expressions of love and affection carved into the trees of Aspen Alley, the prominent grove traversed by Forest Road 801 by Carbon County, Wyoming. Photo credit: Troy Lovata.

Following the Manito Trail

East and West Querencia: USA

I am writing in the kitchen, on the kitchen computer. It is a kitchen because there is a stove and a refrigerator. There was no functioning refrigerator in the first few months of inhabiting this space. I used the porch, which was cold, for a walk-in refrigerator. It worked for almost three months, and then I realized that the dirty, muddy, snow bottom and salt-stained shoes and boots were in the same room as the fruit, celery, coconut water, oat and almond milk, and decided: I do not want to nourish my body with produce and such that has been neighboring with soles that have wandered to and fro along who knows what. I plugged in the refrigerator and now I am in close proximity to an electric box. It will be cold inside that box soon, I think, as I take off my Cal Bears baseball cap, to don a warmer winter hat. I am on the other coast, Eastern, New England region to be exact, however, the Pacific seems to have entered my writing space, Berkley memorabilia cap by the computer, and “California Dreaming,” a tune remembered, warming my heart. West Coast!

Earlier in the day, I had been driving through the wintry scenery and thought how tranquil, I feel at peace just rolling through the towns, the road as my companion and guide for the vehicle’s tires. I realize that as much as I am travelled, this place may be part of my querencia for the fact that I hail from Massachusetts, however, all spaces recalled evoke my querencia. I ride with querencia from Syracuse, New York, to the Florida peninsula, from Miami to Key West back to Tampa and Florida State University. To Georgia and North Carolina, Jersey, Pennsylvania, detour to Ohio and Illinois, where I stop at friends’ property to sleep in my Wyoming truck. I have not visited Washington State or Arizona for a while, but they are a grand part of my querencia as well. Zigzagging at times, right at this moment, the Manito Trail seems pretty stable to me as a route from south to north and then east to west.

The inquiries may be many in regard to querencia. One may ask if they have obtained querencia and/or what would their querencia be at the moment and in moments past and future. Which land, people or space encompasses that abstract reality of something loved and embraced to the sense that one can state, act, feel and see within the mind’s eye and voice, acknowledging: “I am a part.” The notion that a feeling taking one’s mind back in time and then forward, for the mind has no time restrictions, becomes a significant part of my being, my heart, my soul. Querencia? Senses are mine, the energy belongs to me, or it vibrates from the surroundings, and no one can erase my conviction of heartfelt querencia which longs lovingly for landscape, family and país.

Does one develop querencia and then lose it? Is it taken away by bulldozers and backhoes; the sounds of blasts and smell of their aftermath; by construction workers wearing yellow and orange safety nylon vests and red or white hard hats? Could that love of connection be transferred throughout one’s journey on the planet or via a migration corridor? All inquiries fielded could be answered “perhaps” or as the lyrics of the music group Jarabe de Palo’s song entitled “Depende” (1998) states “Depende/Depende ¿de qué depende? / de según como se mire, todo depende” (1998) (Depends/Depends on what does it depend? /on the manner one sees it, it all depends.)

Following the Manito Trail

A Wyoming Connection

I remember attending the Mujeres Activas en Letras y Cambio Social (MALCS) conference in 2016 in Laramie, Wyoming. After presenting on a Puerto Rican writer, Irene Vilar, at the Gateway Center, I had to venture to a new venue, the UW Student Union, the next day. Walking up the 15th Street hill, heading to where I thought was the space, Irlanda Jacinto, one of the organizers for the MALCS Laramie, Wyoming gathering, saw me and brought me to the correct location for the remaining conference events. I had walked past the unknown destination, wandering and looking for a place to reunite with colleagues. The Manito Trail was being made for me, a querencia, without even being aware of the project. It was in that conference that I received news that I would be at that university teaching, learning, and sharing; and yes, the Manito Trail would become part of my mission at University of Wyoming. Joining the community of migrating souls, the first time I heard of the Manito Trail was in 2016, and then I listened intently and connected with Manitos. The Manito Trail finds you. Or there is something in you that seeks the Manito Trail, and you then stumble onto a path of richness, of cultural identity, feeling at peace, safe, as though you have found the place you can define as home. But it is accompanied by a sacrifice of time, hard work and self-development that can be painful as you shed the old ways that do not edify your spirit. That although you may be leaving open space and time, you enter into another that is simultaneously a gift of time and space. And at the end, you realize that it is by grace that you are where you are now; and that is the beginning of my experience with the Manito Trial.

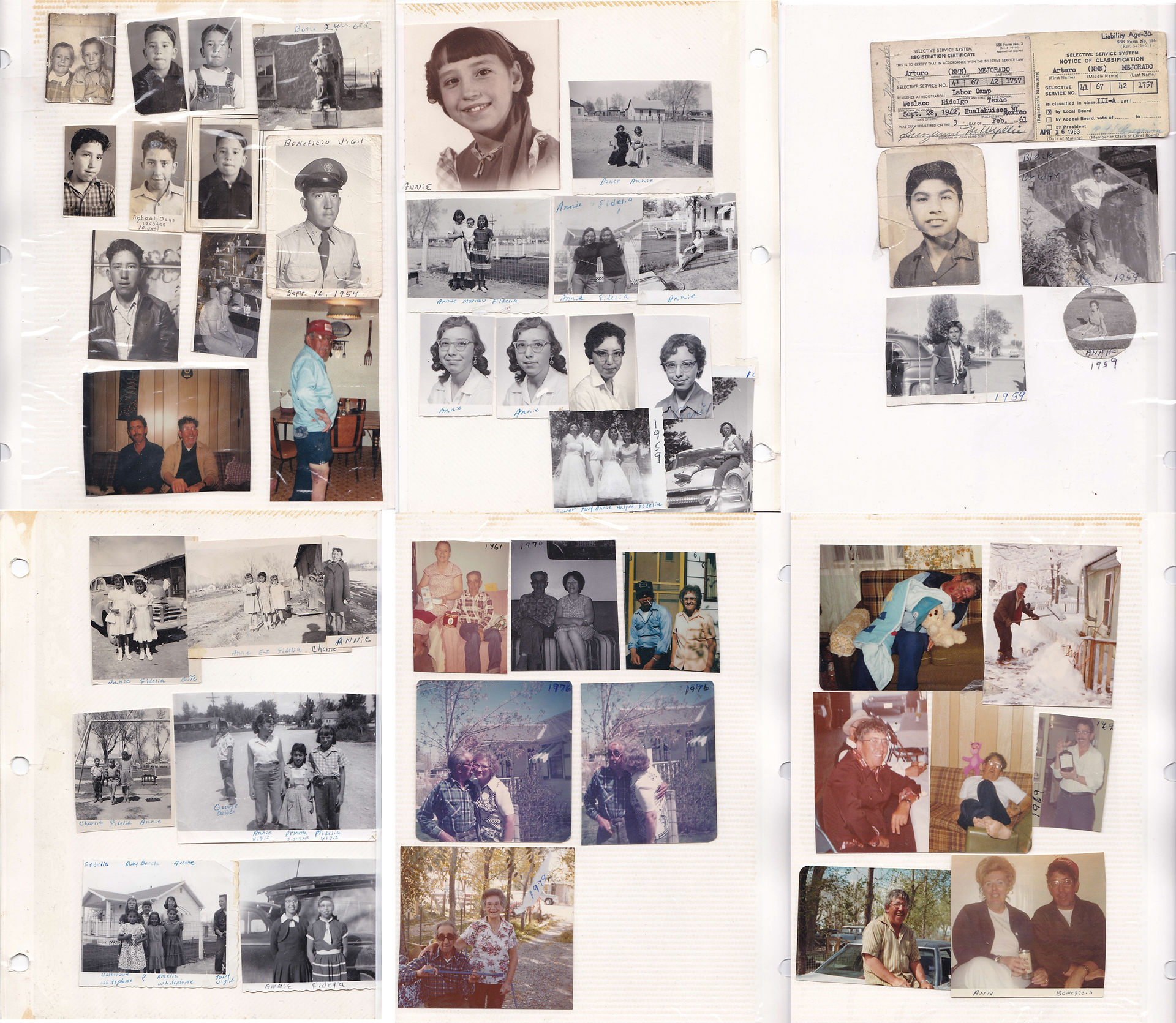

Illustration 2 Annals of Wyoming: The Wyoming History Journal. Spring/Summer 2017, 89:2&3 (88). Photo courtesy of Connie Coca.

When I landed in Wyoming, in Laramie to be precise, I dialed into music, a must as part of my querencia, and I found my Laramie radio station, KOCA 93.5 LP FM, streamed from Fresno, California. Connie and John Coca, founders of KOCA radio station, 93.5 Laramie, Wyoming, were part of the Manito Trail and soon were in my circle, part of my Laramie, Wyoming querencia. In my first spring semester at the University, in two courses, Intro to Latina/o Studies and Chicano Folklore, my students created a radio program and aired it specifically on the bilingual radio station: KOCA 93.5 LP FM. So grateful for that opportunity! Place it on your C.V., I advised the students. My connection continued, as I then listened by sight, as I viewed images displayed in the University of Wyoming Museum in 2017.

Illustration 3 Connie and John Coca. Following the Manito Trail exhibit University of Wyoming Art Museum 2017. Photo courtesy of Ted Brummond.

Following the Manito Trail

Inspiring Learning Journey

I have yet to travel the territory, all I know of the location is via video, photographs, stories, and discussions and dialogue by the founder of the project, Levi Romero, co-director Dr. Vanessa Fonseca-Chávez and Dr. Trisha Martínez, then a graduate student at the University of New Mexico and there’s more. However, that is her story. My story is that I am connected to both: Fonseca-Chávez and I both studied together at Arizona State University from 2008, and I recently met Martínez via Zoom in 2020 through the University of Wyoming. Here I am in 2021, blogging about the journey I had from not knowing what the Annals of Wyoming concerned, to teaching and sharing that edition, that part, that huge fragment of the Wyoming story, the story that belongs and is narrated by Chicanas/os and Nuevomejicanos/as. Therefore, the glimpse that I offer must be continue with another glimpse. Who am I to write about the topic? An educator, a scholar, a child of the Creator connected to the routes of the world as a humble life migrator.

My second year at the university as a one year Visiting Assistant Professor, I had students from a first-year seminar (FYS) visit the University of Wyoming Art Museum’s Teaching Gallery housed in the Centennial Complex on the east side of the University of Wyoming (UW) campus. I embraced the call to follow the Manito Trail not knowing that I had accepted a mission. All I felt upon entering was the joy of Raza in the house! On the wall! (Actually, in the museum!) I humbly ask permission to share my experience following the Manito Trail from the perspective of a Latina/o Studies program instructor in the School of Culture, Gender and Social Justice at the University of Wyoming.

Illustration 4 Following the Manito Trail exhibit University of Wyoming Art Museum 2017. Photo courtesy of Connie Coca.

The exhibition, the murals, the covered collaged wall—big framed, little framed, digital canvases—popped vibrantly for all to glance for a second, to look for three or five, or for those who were intrigued, to ponder for a minute or more and bring the images alive in conversation. I looked, gazed, pondered, analyzed, conversed. I was intrigued. My conversation still continues in 2021. I am still intrigued. Firmly hooked images in a room calling me to engage: powerful colors, strong families and faces of an organized community, leading me to understand a territory, a migratory path.

Illustration 5 Following the Manito Trail exhibit University of Wyoming Art Museum 2017. Photo courtesy of Connie Coca.

I remember the night that I saw images of trees, aspen trees; people, some familiar, Connie and John Coca; sheepherders and homes, and Nuevomexicano/New Mexican images that told the tales about journeys on a trail. It seemed familiar and exciting. Hey, Manito! I encountered these feelings in the American Heritage Center (AHC) at the UW Art Museum and, having been familiar with the center, I then became familiar with the trail, or I realize, that perhaps, I was already part of it. . . Interstate 80 West, from Walla Walla, Washington, to Idaho, through Utah, to Laramie, Wyoming and Interstate 80 East, from Massachusetts to Connecticut, passing thru New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska to Laramie.

To share the stories of Manito initiatives, the voicing of social justice rights of running water, paved sidewalks, fire hydrants that a barrio did not have. To hear songs sung about the New Mexico to Wyoming migration and be intrigued by the explanation and wanting to learn more. Tree branches waving in the wind and branches firmly standing displaying the “here I am, and here I was. Better look at me now because I don’t know how long my Manito carvings will last.” To comfortably breathe because, yes, there is Raza in Wyoming. I would then share that trail with other souls that enrolled in my courses: Mexican American Literature, Chicano Folklore, Latina/o Popular Culture, First Year seminar, and I would indicate the trail for others to walk on. As they walk, waking consciousness to an important populous, students are asked about their narrative, family lore, and where their folk migrated from to arrive in Wyoming, or wherever they may have landed. I shall share by means of curricula and stories of how and why I give scholars the opportunity to read, analyze, dialogue and view the Manito Trail as they discover who they are and create projects expressing their essence.

Illustration 7 Back Cover of the Annals of Wyoming: The Wyoming History Journal. Spring/Summer 2017, 89:2&3 Annals of Wyoming: The Wyoming History Journal. Spring/Summer 2017, 89:2&3.

Illustration 6 Front Cover of the Annals of Wyoming : The Wyoming History Journal. Spring/Summer 2017, 89:2&3

In Annals of Wyoming: The Wyoming History Journal Vanessa Fonseca’s article, “‘Donde mi amor se ha quedado’: Narratives of Sheepherding and Querencia along the Wyoming Manito Trail” (pages 6-12) explains the trail of Nuevomexicanos from their home state New Mexico to Wyoming and reason for travel and temporary relocation. The voyage north was in search of labor and economic opportunities and Fonseca focuses on “how one develops a sense of place, particularly outside of their home environment” (6) and shows that “maintaining a sense of place for nuevomexicanos is pivotal to their cultural development and preservation” (7). The Manito Trail is considered I-80 and I-25 lanes travelled to and from Guayama (the spelling of the pronounced Wyoming by the Manitos) and Nuevo México (New Mexico) to renew querencia (11-12). The article shares the Manito diaspora story and recognizes the select families mentioned in the article arriving in Wyoming in early 1930s through the 1950s “exhibited their querencia to New Mexico through architecture, culinary traditions, art, and language” (7).

In Fall 2017, as part of my First Year Seminar course, I uploaded the special edition of the Annals of Wyoming, Spring/Summer 2017, and would not have known about the journal were it not for the Following the Manito Trail exhibition and because an editor asked if I would like to contribute to that edition. I had only been in Wyoming for two semesters, and then in Fall 2017 there was a virtual conference NACCS (National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies), and I was on the Wyoming panel and Following the Manito Trail was mentioned as well as other Raza Wyoming stories. That fall was Cheech Marin’s exhibition AND the exhibition for Following the Manito Trial.

Following the Manito Trail

Announcement Grand Opening Celebration August 19th would be the date of my first entry on WyoCourse “Announcements” to the students concerning FOLLOWING THE MANITO TRAIL. It was my first time teaching the First Year Seminar: Latina/o Popular Culture course. It was Fall 2017, and I didn’t have an official announcement for what I later found out was a “Grand Opening.” WyoCourse Announcement:

“Latina/o Exhibit at UW Art Museum” Fall 2017. The following highlights significant developments in Mexican folk culture, Chicana/o cultural arts, and New Mexico’s historical Manito Trail into Wyoming."

Changing Faces: Traditional and Contemporary Mexican Masks

August 12 – November 12

· Conversations with Curators, November 1, 12pm

Papel Chicano Dos: Works on Paper from the Cheech Marin Collection

September 23 – December 16

· Art talk, September 21, 7pm, Education Auditorium

· Gallery walk through, September 22, 10:30am

Following the Manito Trail (AHC Exhibition)

August 12 – November 18

· Panel Discussion, Following the Manito Trail: a conversation with researchers, September 22, 5-6pm, Stockgrowers Room

Illustration 10 Dr. Margarita E. Pignataro with Cheech Marin. UW Art Museum, Grand Opening Following the Manito Trail 2017. Photo courtesy of author.

As the Wyocourse announcement states, the exhibition Papel Chicano Dos: Works on Paper from the Cheech Marin Collection coincidedwith Following the Manito Trail in the same months. Raza energy definitely circulated in the museum and poured out to the streets of the town. My second year at the university was truly a blessing; to have experienced two powerful exhibits.

I have since incorporated both the Papel Chicano Dos and the Following the Manito Trail materials in my five courses, something I did not consciously calculate during that grand opening, and yet, it was a grand opening for my professorial development, in the classroom and in scholarship. I have taught querencia and Following the Manito Trail since 2017, and even though I may not require the participants of my courses read the Annals of Wyoming: The Wyoming History Journal, I mention querencia, for example in my African Latino Caribbean Literature course where we read Nancy Morejón’s text Querencia/Homing Instincts (2014). Whether in a classroom or in a Zoom room, querencia is always a topic well incorporated since it is about home, a place of belonging, the sense of being free of cares and welcoming the surrounding and the surrounding welcoming the being. Well appreciated, I find ways to include the important part of Wyoming history in a University of Wyoming course, but also the extension of the route to the southern states where the radius widens. I now travel to the Manito Trail from afar—

Following the panel discussion, Following the Manito Trail: a Conversation with Researchers, I had a bit of querencia myself that evening: I met a Chilean in Laramie. How special that Chile is connected to Wyoming. By October 24, 2017, I had Chilean empanadas to offer the students in the First Year Seminar LTST course, made from the Chilean I met that September 22nd night in the center of the town. That night querencia was in the air and I found it in Laramie. Eyes wide open in astonishment, and then again, of course, it has always been my heart’s desire to find Raza wherever I may wander. I went to an after gathering at a pub, and there was pique on the table, and some ladies, colleagues of mine, had informed me that they had eaten Chilean empanadas. Empanadas chilenas in Laramie!!! If that was true, bacán (awesome/cool). I now believe that the town could be named Laradise. How did that arrive to a table in downtown Laramie near the railroad tracks? I wanted to find out. More on that story in the next set of entries. All of this happened that night that I discovered that I was placed on the Manito Trail. (I also met an Argentine at the Following the Manito Trail event and connected her to another argentina that I had met while riding my bike through a field off Hardy Street in 2016. Wonderful. Getting digits in the first meeting from compatriots results well, or if not compatriots, close to it. . . .¡Cono Sur presente!) ¡Chile presente!

Following the Manito Trail

Back on Track

Back on track, sorting through past years’ assignments, I submit all the tareas that I have had for Following the Manito Trail. Dr. Martínez, be sure to place Massachusetts on the map. I believe these are all, for now that is. I am sure there will be a second set of entries for future courses and/or a deeper dive into the words written in the present entry. It is always exciting to teach the statehood happenings and to travel from one region to another. For the audience to relate to one thread of the topic is joy, since after that thread they realize there may be many more. When I plan to incorporate the Manito Trail, I think of the whole essence of identity, which is layered and potentially complicated. Or as Fonseca-Chavez states in her book Colonial Legacies in Chicana/o Literature and Culture (2020), “fragmented.” There are many stories and one people.

Comments