Following the Manito Trail: A Life of Manito Service

- Isabelle Sandoval

- Sep 29, 2021

- 5 min read

Isabelle Sandoval

Retired Educator

Santa Fe, NM

After washing the frijoles and chile colorado dinner dishes one evening in 1968, I started working on my high school English assignment at the dining room table. I opened the book cover of A Tale of Two Cities to read for English. I asked my father if he had read the book. He answered “no” and turned on the TV to watch the evening news as he balanced a bowlful of roasted piñón on the arm of his recliner chair.

Turning the pages of the worn paperback book, I read the first chapter while noting key points for the class discussion. High school was mediocre. Most of my grade school classmates had been tracked into lower basic classes. I had been placed in regular classes with students whose parents were doctors, professors, teachers, and service workers. These students lived in new homes on the other side of the railroad tracks. My neighborhood peer social connection was the monthly Spanish Club meeting when I gathered with Lincoln Elementary School friends from the West Side.

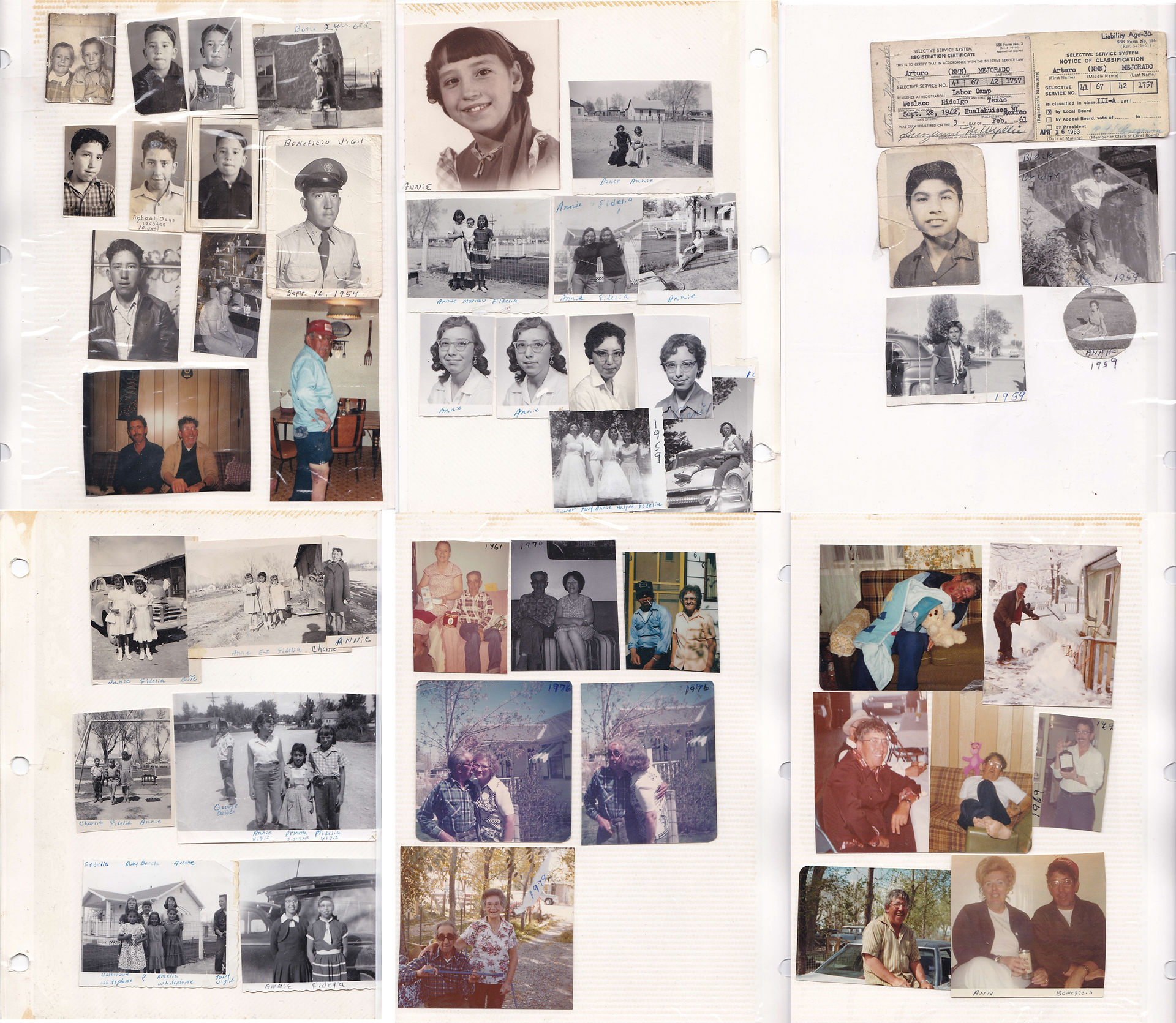

From the corner of my eye, I observed my father scanning the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) monthly magazine while a hill of empty piñón shells grew on the worn album cover of El Corrido de Daniel Fernández. As a devout member of the VFW, Daddy faithfully attended meetings wearing his VFW cap. When a veteran died, he attended the funeral dressed in full uniform. He would sell the signature veteran papier-mâché red poppy to others for the purpose of raising money for needy and disabled veterans on Memorial Day.

Dad's Red Remembrance Poppy and the Family Crest

I watched my younger siblings until my father arrived home from work while my mother worked a noon to evening shift; she left homemade dinners like alberjones, fideos, and posole ready for me to warm. Truthfully, as a teenager more obsessed with school and friends, I was embarrassed that my father appeared trapped in a World War II cocoon spanning several decades. I sensed that he did not understand my difficulty in attending high school. My homework time started after watching my siblings and washing dishes. As I read the words of the book, I wondered how this story would make a difference in my life.

Decades later, after being humbled by graduate school, divorce, single parenthood, and the death of my mother, I connected with my father in 1982. He had moved back to New Mexico by then. I had learned that real life events meander through the peaks and valleys of individual experiences and are channeled by societal transitions.

As I spent quality time listening to my father, he shared with me that he had moved to Wyoming after World War II because there were no jobs in New Mexico when he was discharged from the Army. With little money and a used car, he moved to Denver for a month and was told that landlords did not rent to Mexicans. With no job or a roof over his head, he drove the car northward to snowy Wyoming because he had heard from relatives about jobs in Laramie. When he arrived, he quickly learned that Mexicans in 1946 Laramie would not be seated for a haircut at the town barber shop. It would be one of the first of many hard lessons he’d learn in Wyoming.

Listening to my father’s story, I was struck by his candor at recounting the indignities he had encountered. Between the Denver and Laramie stories, I couldn’t help but think of the Tale of Two Countries manifesting in his journey along the Manito Trail. I was astounded that, despite this treatment, my father had displayed such unselfish community service. I had worked with and studied under dynamic scholars and leaders, but was unprepared to grasp the degree of noble individual service my almost invisible father gave to his family, country, and community without expecting any financial gain or community honor.

In 1941, during the Great Depression, Dad enrolled in the Civilian Conservation Corps, the public work program initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Thanks to the CCC, he was briefly able to return to La Querencia: Dad worked at a Santa Fe site for a year for the sum of $30 a month. He sent home almost all his earnings – $25 a month – to help care for his disabled parents and younger siblings.

From there, Dad served in the United States Army from 1943 to 1945 to defend his country. He allocated half his Army pay for his widowed mother and the remaining half for his new bride. He served in the Pacific as a sergeant supervising twenty-six men. After being administered an English I.Q. test as a second language learner, he scored in the superior range and was asked to participate in Officers’ School. In his letters to family, he expressed how he missed his chile and hearing his favorite Adelita song. He decided to serve as a soldier and return home to la tierra encantada of Las Vegas, New Mexico, never traveling further than Albuquerque or Colorado to visit family.

Dad was a man of many hats

After leaving the Army in 1946 and moving to Wyoming in search of a job for his family, my father took the civil service exam for the United States Post Office. With a score of 99 on the exam, plus bonus points for veteran service, he exceeded the numerical job entry requirements. While working at the Post Service, Dad also served on the Laramie School Board from 1969 to 1970. He had an acute interest in high quality education, especially when it came to the fairness of building accessibility and instructional services. Prior to serving as a board member, he had a family member diagnosed incorrectly as a special-needs student who needed placement in a special education school for low functioning students. Dad appealed the decision to the school principal and the student was placed in gifted and honor classes. As a school board member, my father advocated for financial parity of Lincoln School on the West Side, promoted equity of minority gifted student services, and advocated for the implementation of pre-school services.

The bell awarded to my Dad after his time on the Laramie School Board

When Dad retired from the Postal Service in 1978, the Laramie Boomerang wrote that “he was the friendly man who had the longest line of patrons and would be missed.” He traveled to Alaska, Puerto Rico, and Europe. In the lovely city of Toledo, Spain, he shared a conversation with a stranger. The Spaniard told him that he was a man of cumbres altos or high summits and must live among the eagles of Toledo and New Mexico. He did just that: Dad spent the remainder of his life in New Mexico, where he passed away in 1999. His only request was to be buried at the Santa Fe National Cemetery. There he rests under the high peaks of the Sangre de Cristo Mountain Range.

Souvenirs of Dad's time in Toledo.

Out of necessity and duty, Manito soldiers left their beloved New Mexico homeland to make a better life in another state or country for their families and communities. Gracias, Manito soldiers, for your service. May the memory of all Manito soldiers – including my father, John Sandoval – forever be a blessing.

My dad, John Sandoval, working at the Post Office after leaving the Army.

Comments