Following the Manito Trail: 1950 Laramie West Side Cafecito

- Isabelle Sandoval

- Aug 25, 2021

- 3 min read

Isabelle Sandoval

Retired Educator

Santa Fe, NM

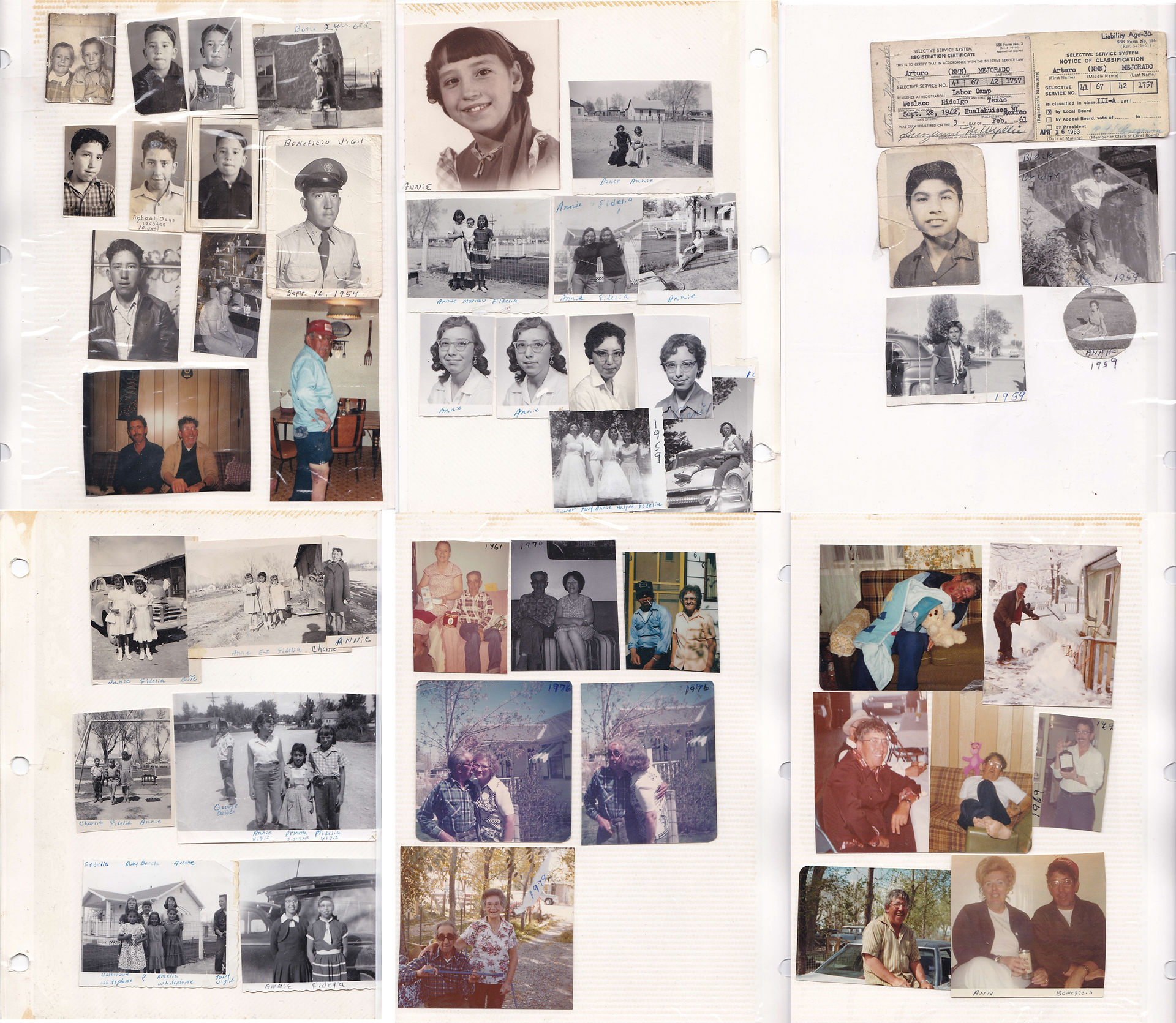

Schooling begins at home and is shaped by complex societal standards. The role of the female in society transcends boundaries and community opportunities. In 1950 Laramie, Wyoming, besides being primary caretakers, Manita women worked for salaries outside of the home as maids, cooks, dishwashers, laundresses, and cleaning help for restaurants, hotels, the University of Wyoming, doctors, and families.

As a young girl born and raised in the 1950s in West Laramie, I was awed by the energy of Manita women. Most Hispanics and economically challenged persons in Laramie lived in the low rent housing on the West Side of the city, adjacent to the railroad tracks. Lacking cars, West Side women and children pedestrians were connected to downtown by the viaduct and footbridge. The essential element of respect was observed on the West Side. Children recognized adults by honoring the family. Family members called their neighbors Don Marcos or Doña Marta as an archaic linguistic hallmark of New Mexico culture.

Our vecina's Westside Laramie house

The diverse neighborhood consisted of New Mexicans, southern Colorado residents from the San Luis Valley, families from Mexico, and Anglo residents. By 1948, Victor and Mary Ybarra sold a building on West Fremont to Flora Hayes of the Church of God in Christ. Black church members on Sunday morning graced the neighborhood with melodious songs, preaching, and extraordinary rummage sales.

My beautiful red-headed, ivory-skinned mother worked in a hotel restaurant as a cook and commandeered the household needs with her requests by prefacing her wish with mi hijita or que muchacha. As a girl, I was nurtured in the normative feminine culture of my home. My parents spoke Spanish to each other, friends, and family. I was encouraged to answer my parents in English because my parents had been punished for speaking Spanish at school in New Mexico. It was assumed that English was the gateway to a better future.

Monday morning was dedicated to washing clothes in the basement. Tubs of white clothing soaking in Clorox were washed for the week. Piles of family laundry were separated for washing, from light-colored bedding to dark clothing. After washing with powdered detergent in the Maytag machine, each article of washing was placed through the wringer and deposited in a clean tub of rinse water, then put through the wringer again. Cotton apparel, like shirts and dresses, were saturated in a tub of cooked starch and put through the wringer a final time. The laundry was hung outside with wooden clothespins on the line to dry.

Drying clothes in Wyoming was difficult. If the weather was snowy, clothes had to be hung in the basement to dry because the outside temperature froze the clothing into stiff, coarse ice that pierced the hand. Cinders from the nearby steam engine trains often rained rough black confetti deposits on the laundry. Dirty cinder laundry had to be rewashed.

Nuestra cocina - our kitchen.

Hanging the clothes outside provided women the opportunity to talk. With their husbands working at the railroad, the cement factory, hauling trash, or elsewhere, the women could speak freely. Manitas chatted outside to plan a cafecito later in the week at a designated time.

Quarterly fancy cafecitos were attended by a handful of close amigas. Weekly cafecitos were attended by Doña Luisa, prima Esperanza, or tía Mary. Coffee was made in the Pyrex glass coffee maker or the electric coffee pot. Chipped cloral porcelain cups and saucers, discarded by the university, were placed on the kitchen table along with paper napkins and spoons. Matches and an amber glass ashtray accentuated the ambiance.

Authentic chipped sorority cup from the University of Wyoming, donated to my mother.

Children were shooed away while the women drank their cafecitos with canned milk and sugar. As women shared their weekly schedules and problems, the swirling smoke of Salem menthol cigarettes rivaled Freudian psychotherapy: the untrained women expertly psychoanalyzed problems and rendered possible solutions. As their red lipstick tinged the coffee cup and cigarette butts, the vecinas appeared ready to confront the trials of the week. Tears, laughter, and cries resonated throughout the dynamic Spanish conversation. The women hugged each other at the end of the hour visit, and their cigarette packs were returned to the fancy apron pocket.

I remember Doña Luisa leaving the casa wearing her purple wool coat with the Peter Pan leopard print collar. I asked my mother if she really did teach school in Mora, NM during World War II. Her eyes sparkled remembering her teaching. I was scared to ask her why she did not teach in Wyoming.

My heart danced to the future song of Disparity of Manita Opportunities. Wyoming Manita rock and roll was born. The good old days would soon be obsolete.

Comments