A Barrio Testament

- levi romero

- Nov 14, 2016

- 4 min read

South Park Improvement Project: A Barrio Testament

My wife Jeana Rodarte was born and raised in Riverton, Wyoming. Both her parents’ families had migrated from Gascon, a small village outside of Las Vegas, New Mexico. Her grandfather, Valentin Rodarte had moved to Riverton in the early 1930s to work in the Sugar Beet industry. Arriving in Riverton, they lived in a railroad car until they could save enough money to buy a house. The younger Rodarte siblings found picking betabel too laborious and soon were able to gain other forms of employment. It was not long after when they met and married their spouses. My wife’s father, Margarito “Mike” Rodarte, married Clorinda Trammell. His brother Ben Rodarte, married Dorothy Apodaca. Their sister, Beatrice married Jimmy Martinez. Their youngest sister Helen, married Emilio Vigil.

I first met the family when Jeana took me on an extension of our honeymoon to meet her tíos, tías, y primos. We spent almost a week amidst her family, friends, and relatives that composed the manito community of Riverton in the area known as “the barrio.” It was there when I began to ponder how the Nuevomexicano culture had survived so far removed from its native homeland. The language the older generations of the barrio spoke the same dialect of northern New Mexico Spanish. They ate the same traditional New Mexican foods, chile verde, chile molido, chile pequi, papas fritas, papas con spam, papas con weenies, papas con cornbeef, papas con de todo. Frijoles, chicos, tortillas, macarones, arroz dulce, yela de capulín. Y hasta potted meat, Vienna sausages, and an assortment of other similar foods lining the trasteros of northern New Mexico kitchens. Their homes were furnished and decorated with the same santos and religious iconography found in New Mexico homes. On Friday nights, the young women convened to pray the Rosary at someone’s home. The Barrio residents kept small, backyard garden plots where they grew tomatoes, chili peppers, calabasas, calabacitas, maiz, frijol, alverjon, and other vegetables. And the Spanish music they listened to came from New Mexico. In the fall they sent requests to their New Mexico relatives for chile, piñon, and the latest village mitote.

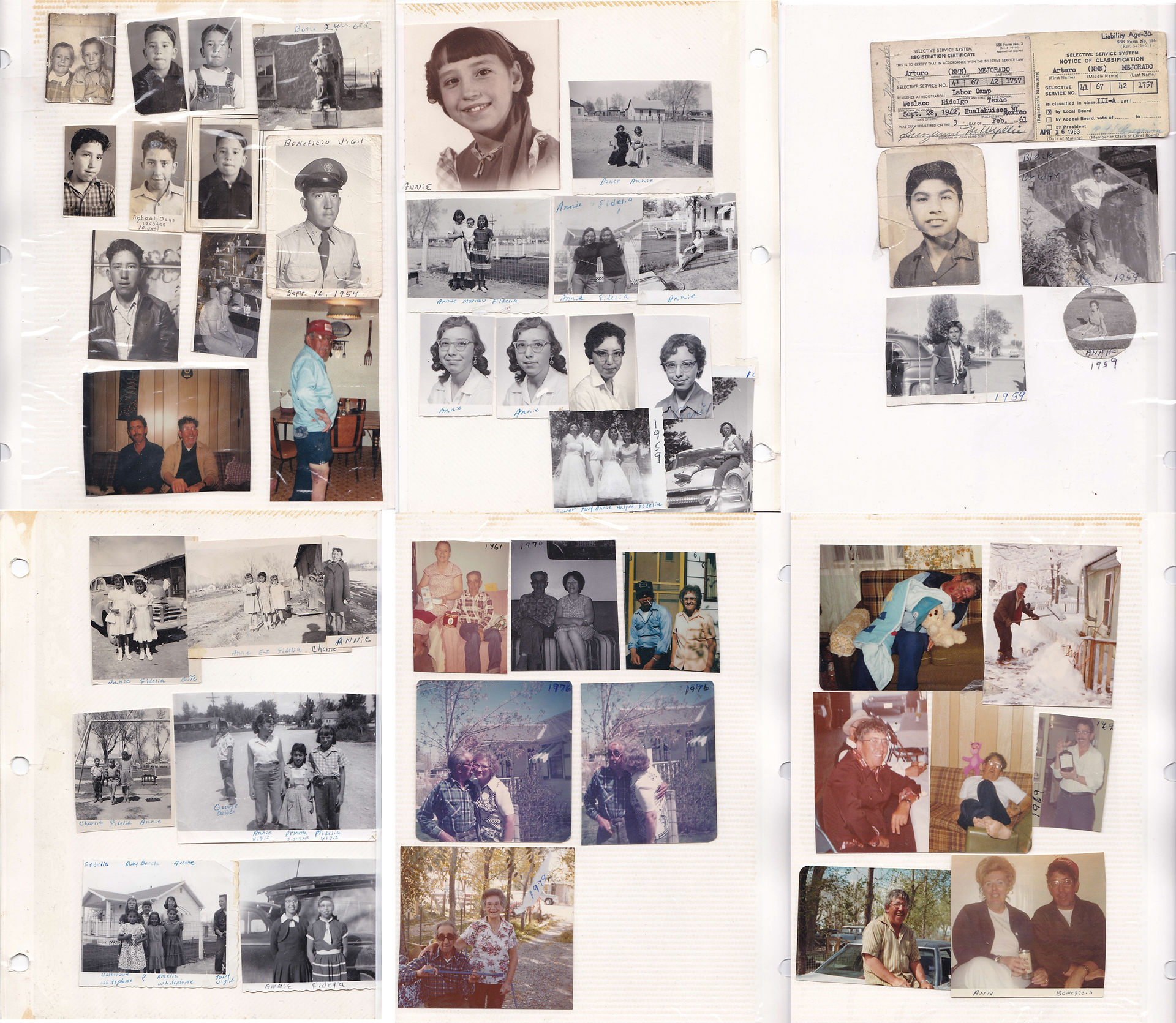

As the years rolled on, I became more and more fond of our visits to Riverton. The feeling of familia. The fishing excursions that awaited. The laughter. The stories. Uncle Emilio’s never-ending stories. Full of humor and insight. They spoke of a time that evoked a strong sense of community among the manitos living in the barrio. Of all-night poker games, hunting trips, fishing outings, and camping excursions to the Sinks that included games such as the spoon and egg relay, the three-legged race, the egg toss, and bike races down the switchbacks. They recalled stories of bar fights and someone getting their lights knocked out that ended in a chorus of laughter. The names they dropped during my visits over the years became familiar. It seemed as if I had even known them. Granpa Pipes, Grandma Angelica, Bonay, Fishy, Chiefy, Grandma Cookie, Doña Franque, Uncle Jimmy, Moises. They were more than just names remembered in conversations or faces captured in faded black and white pictures peering out of a dusty photo album. These were people who had formed a kinship amongst each other that was time everlasting. Their bonds had been cultivated and nurtured by the need to share of what everyone had in the best interest and wellbeing of their community. The Barrio.

And, perhaps, no story evokes the sense of community more so than the South Park Community Development project initiated by residents of the neighborhood known formally as the South Park Addition. Finally, in 1986, after many years of arduous obstacles and setbacks the City of Riverton agreed to provide sewer, water, and street paving to the neighborhood. However, despite numerous requests by residents of the Barrio, the City of Riverton refused to provide sidewalks, curb and gutters for the newly paved streets. The residents sought out donations of materials from the local cement factory that used the Barrio roads and from other local businesses. The residents agreed to provide the labor and skills. After coming home from their long days at work, the men formed the construction crews while the women cooked meals and provided assistance. Driving down any of those streets today, it is taken for granted that it was the Barrio community which is responsible for the infrastructure that exists in South Park.

A 30-year anniversary gathering was held this past July at Monroe Park in celebration of the South Park Improvement project. In attendance were men and women who had worked or contributed to the project in various capacities, their children, grandchildren, friends, neighbors, and the lives of those who are no longer present were acknowledged and fondly remembered. The project endures as a testament to the strong work ethic and resiliency of manitos working together, side by side to create a home for their families and their community.

South Park Improvement

Side by side we work together

On the streets of South and West

Until the work is finished

This crew will never rest

Hard work is all we met

People will tell you that

Annie is always with us

Ready for this and that

Keeping the gang together

Is Emilio’s everyday chore

Making sure we get enough cement

Perhaps a little more

Remember we are doing this

Our way and without pay

Very little time is wasted

Everybody is there each day

My last favor I will ask you

Everybody please cooperate

Never try to over-do-it

Time can always wait

Jimmy Martinez

Comments